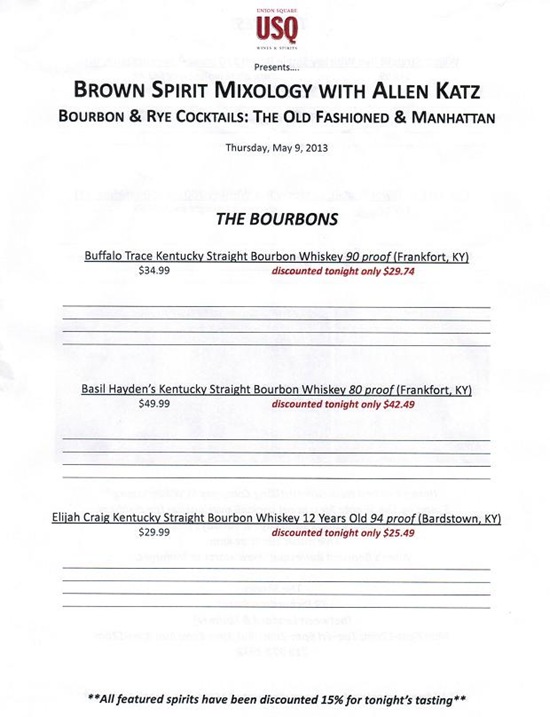

As a whiskey fan, I’ve sometimes experienced something of a love-hate relationship with rye. Its spiciness made it not quite right for me to sip on its own and quite honestly, the only cocktail I’ve been able to drink with it is The Sazerac. Being the open-minded kinda guy I am, I decided it was about time to give it a fair shot – that’s why I attended a tasting called Brown Spirit Mixology at Union Square Wines & Spirits. The tasting, conducted by Alan Katz (one of the founders of Brooklyn’s New York Distilling), analyzed the two spirits in order to help us understand why they worked well in certain types of cocktails. However, the portion that I’ll focus on in this blog post is some of the background and technical information around American-made whiskey.

Katz began the evening with a brief review of the manufacturing process. Whiskey is made from grains – corn, rye and barley – starting with fermentation. With grains, the fermentation process takes the sugar contained in them, mixes it with yeast (which eats the sugar) and converts it to alcohol. The next step is distilling. Distilling further refines the alcohol. Very often you will hear alcohol manufacturers brag about multiple distillations of their spirits, but the fact is that the more a spirit is distilled, the less flavor it contains. A single distillation extracts a certain amount of alcohol from the mash (the cooking of the grains); it’s like wringing water from a washcloth – you may get out anywhere from 90 – 95% of the water, but rarely 100%. A 2nd distillation removes 30% of the alcohol, resulting in a 140 proof spirit; it is then diluted to get the alcohol content down to 125 proof in order to comply with the law.

As with any industry, this one tends to have its own unique terminology; very often, you might see a label that says “straight bourbon” or “straight rye”. What does this mean? “Straight” by law means United States whiskey contains a minimum of 51% of its main ingredient – this of course means rye for that spirit or corn with respect to bourbon.

Some bottles may even be labeled “Bottled In Bond”. “Bottled In Bond” refers to a government act of 1897 requiring a federal bond agent be present in every distillery to essentially audit the spirit producer’s manufacturing process. This would include checking the paperwork and ensuring that there are no impurities to verify that what is actually in the bottle is precisely what a manufacturer claims it contains. Nowadays, however, the term is generally used as a designation of the alcohol’s level of proof – 100 proof whiskey.

Since the taste of wood in the spirit is an important feature, many connoisseurs want to know when a whiskey was barreled and when it was bottled; this is considered important because the weather can impact how flavor is imparted to the spirit from the barrel. How many weather extremes – specifically, summers and winters – did a particular whiskey experience during its aging process?

With respect to aging, there are also specific regulations that must be observed by a whiskey manufacturer. In the United States, bourbon or rye must be aged in a new barrel, for example. This rule came about back in 1964 due to unions – government representatives from the states where these barrels were made pushed for this regulation in order to keep employees from these states working. The barrels are made of new American oak. Why oak? Well, to some degree, it was because of the strength of that wood, but in part, it also occurred as a result of chance because oak just so happened to be most of what was planted at the time, so it also became somewhat of a forestry issue. Since the barrels always must be new, they can never be used again to make American whiskey once they have been emptied. As a result, they are instead resold around the world to be used in the aging of scotch in Scotland and rum in the Caribbean.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Speak Your Piece, Beeyotch!